Sculpting to Scale

Irish-born Corban Walker explores ‘life-size’ art. By Blake Gopnik

Corban Walker has something every artist needs: a critic trap, stretched taut across the ground floor of his studio in Brooklyn. A barrier of steel wires runs the width of Walker’s front room, from about chest height to the level of a tall man’s head; in a moment of distraction, this critic almost got his face egg-sliced. Walker, however, doesn’t have to worry about his own safety, because the bottom wire is set at what he calls “Corbanscale”—it barely grazes the top of his head as he passes back and forth underneath.

Forty-five years ago, in Dublin, Walker was born with achondroplasia, the major cause of dwarfism. He is four feet tall. “The core of what I’ve been doing over the last 20 years is about this: my measure and the rule laid out for the average indi- vidual,” he says. And his art is about how that “rule” doesn’t fit him. He says that the wire piece, called “Latitude,” is possibly the most confrontational of his works about stature: “You could grate yourself [on it]—but I can’t.” But just about everything he’s made is a nod to his height, or at least to the number four, which describes it.

A work in progress in his studio is a lat- ticework cube made of plastic orange rods, designed so that there’s one natural view- point at Walker’s eye level and another at a more “standard” level—the confrontation of “Latitude” seeming to yield, in this piece, to conciliation.

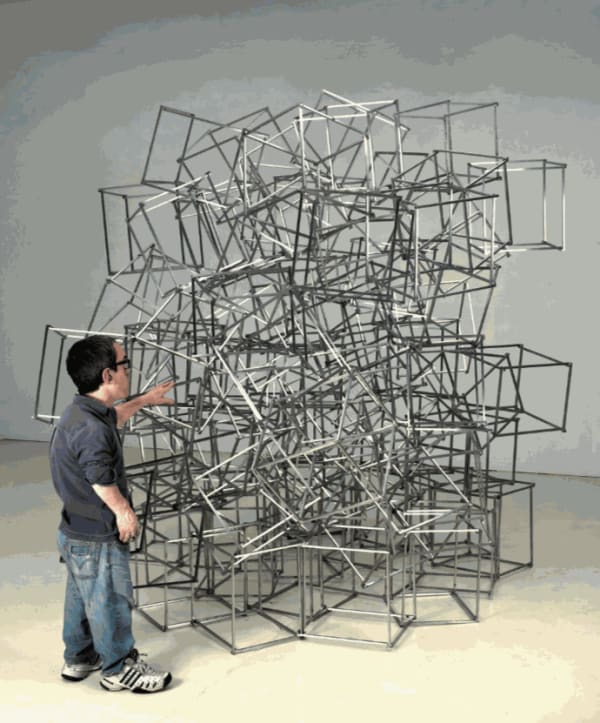

Walker’s most prestigious commission came in 2011, when he filled the Irish pa- vilion at the Venice Biennale with a pre- carious pile of 176 cubes built from stainless-steel rods, stacked almost to the rafters. The heap was inspired, Walker says, by the 2008 financial collapse and the un- stable state of the global economy. But the number of cubes is, of course, a multiple of four, and the pavilion’s windows featured geometric cutouts based on the 4-foot Cor- banscale. The Venice works, like every- thing Walker makes, have aesthetic roots in elegant 1960s minimalism, but they matter now because they update that tradition and anchor it in life as it’s lived. “He’s using his rule and his scale to find his own narrative within that minimalist history,” says Eamonn Maxwell, the Irish curator who organized the Venice project. “He plays with his height, but can also ignore it.”

Walker, who sports Coke-bottle glasses and a scruffy red beard, says that most people take the size of the built world for granted, whereas he’s always had to deal with its fit. His father was a well-known Irish architect who’d worked under Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe, modern- ist masters who conceived their buildings around the height of a six-foot “able-bod- ied man,” Walker says. That same conception governed the art-filled house his father built for his family—“a concrete ceil- ing with four glass walls”—the only concession to a diminutive child being a plenitude of stepstools. “They also put in a second doorbell that was lower,” Walker remembers, laughing. His stature, Walker says, “is certainly a normal part of who I am, and a normal part of how other people engage withme...I work with it,but I try to make it something that doesn’t control my life.”

In conversation, Walker doesn’t particularly avoid the subject of dwarfism. He voices admiration for the vertically challenged star Peter Dinklage. (Walker himself once acted alongside Gabriel Byrne and a young Matt Dillon in a “very respectful” film about a dwarf, “to make some money, when I didn’t have any.”) And he discusses his single visit to a Little People of America conference, where he was actually on the tall side. (“I found it to be quite insular, and not very useful to me.”) But shortness isn’t a topic of unending interest. Yet Walker does talk about frustrating times as a young adult at Ireland’s National College of Art and Design, in the early ’90s, and how “this measurement was what was standing in my way of fully participating in the art college, or Dublin.” He remembers one Christmas when he rooted himself in front of an animatronic display of Snow White and her seven helpers, forcing shoppers to recognize the presence of a real, uncomic dwarf. A recent work is almost as direct: a tall video monitor with Walker displayed on it, life-size, and demanding that viewers come to grips with what “life- size” is for him. “Because it’s shot at my eye level, my gaze is unavoidable,” he says.

After becoming a notable figure on the Irish art scene—“very, very well respected and known,” Maxwell says—Walker moved to New York in 2004, partly because mate- rials were easier to find, but also to nab a collector base for his ambitious in- stallations. He’s had some modest success: he shows with the presti- gious Pace Gallery and has had work in two exhibitions at the Flag Art Foundation—including one, called “Size Does Matter,” which Shaquille O’Neal had a hand in curating and for which Walker made art about their re- spective heights. “Corban had a serious vision for his piece,” says Stephanie Roach, the director at Flag, “but he had a sense of humor about it.” She de- scribes an apparent connection between the tall athlete and short artist. “The two of them looked at each other, with three feet of difference, and it’s as though they both had a particular way of looking at the world.” She also notes that Walker’s work, though clearly about his own experience, doesn’t come with a big dose of autobiog- raphy and isn’t overwrought. “It relates to him, as a person in his body, but he leaves

room for a viewer to interpret.”

Walker says that his height is “not necessarily the be all and end all of my work ... The more I carry on working, the more I want to explore other things that interest me. There are only so many things you can do about a person who has a diminutive stature.”