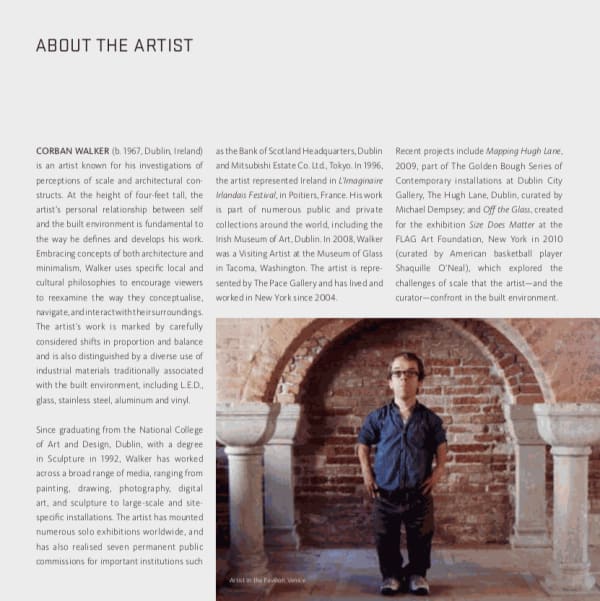

Corban Walker

“Man is the measure of all things”, went the old humanist creed. Then, removed from nature’s pinnacle, man became simply a reed, but, as Blaise Pascal put it, a thinking reed. Further devalued, no longer an emblem of spirit, the body became just a portable assembly of viscera and organs.

Yet the body as measure, empirical interpreter of distance, height, location, has its uses. Its idealistic aura long gone, it is human engineering’s rule of measure, of median percentiles standardising the design of its immediate environment. For architecture, Le Corbusier invented his modular man, the denatured emblem of Renaissance man. Now Corban Walker, the son of an architect, establishes himself as measure of his own art his body as mirror, unit, module, standard. With this insistence—it is nothing less—he remakes his environment according to his own measure. This we all do so some extent. Paintings are hung too high for some, too low for others. Scissors punish the left-handed. Seats (including aeroplane seats) make no concessions to the very tall. The list can go on. The world of the basketball player is not our world. Nor is the world of the very small. The shadow of Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver falls across our world every day. This is a preface to citing the fact that Corban Walker is four feet tall.

To make a disadvantage his advantage is intrinsic not just to Corban Walker’s art but to life as he lives it. As an equal member of any community through which he may pass, Walker asks no concessions, nor does he give any. Part of this may be due to his extraordinary parents—his father Robin was a distinguished architect, his mother Dorothy a well-known cultural critic. One of Walker’s early artworks was a small step he made to accommodate his size. It gave notice that his redesign of the world would fit his own corpus, not necessarily yours or mine.

Walker first declared his presence on the New York scene at the Pace Gallery in 2000 with Mapping 4. A glittering environment of glass modules—fourteen feet high, four inches wide—leaned (leaning and stacking are his verbs) against the gallery walls to produce a standoff between order and disorder—a good look if you can achieve it. The leaning angles varied. The intervals were irregular. Transparency and reflection, the light-trapping density of glass, its ultimate opaqueness when stacked, are properties so insistently appropriated by Walker that they have become his emphatic signature. The gallery was dissolved into a wilderness of reflections. One of the most daring exhibitions of the year, it was obsessional and relentless, an act of will without being willful. In its sharp edges and sometimes perilous leans, it was dangerous. The threat of splintered chaos was held in abeyance. A soundless piece implicitly invoked sound. The result was a kind of mad beauty that avoided the decorative, a seduction glass slyly offers.

Sometimes popular art and fine art attempt to converge and end up intersecting, each then going their own way. The crystalline, light-struck arctic environment designed for the Superman movie (1978) touched on Walker’s concerns and then moved on. But where in this uncollectible extravaganza at Pace was the figure of the artist? Yes, the four-inch wide glass was a twelfth of his height, but he answer was in the gallery’s central square column. A peephole at the artist’s eyelevel compelled us to bend (itself a metaphor) for viewing. What was seen? Nothing came into exclusive focus. The act of bending and looking at the installation was its main content.

Walker walks the world at a different scale from most people. That’s obvious. What’s not obvious is how his pedestrian experience defines his survey of the terrain. Ramps and staircases frequently attract his attention. Two permanent installations (Scales in Tokyo, and Stair, in Cork, Ireland) take the staircase as subject and model. On the adjacent walls, glassy units climb the stairs in the same rhythmic progression. Ascending and descending, the user’s reflected image strobes by. Human engineering pays a lot of attention to the height of steps. They are usually set at median percentiles. Step-height, width, and degree of inclination are the basic variables. Such decisions are always under inquiry and are revised according to the community they serve. Our predecessors, a foot shorter, would scale their environs differently.

For one of Walker’s most interesting “stair-pieces” Off the Glass, he found a partner, the basketball player, Shaquille O’Neal—all seven foot, one inch of him. The exhibition “Size Does Matter” was curated by O’Neal in 2010 for The FLAG Art Foundation in New York. Ascending along the wall step by step, vinyl markers incrementally climbed from Walker’s four feet to O’Neal’s seven. A more complexblue and green vinyl drawing on the opposite wall conjugated their height differences inventively.

In this, as in other works, Walker’s revisioning of accepted norms is as sharp as the edges of his glass. He bends the spectator to his will. This aggression is dissembled, but it is there. Walker’s revised scale is not a humorous ploy to be indulged; it is deadly serious. How this is enacted in his work through his modular repertory of glass and mirror —incremental rotation and reversal of planes—is easily read. It is done without rancor, which rhymes with Walker’s amiable and optimistic temperament. Never accusatory, his work is a testament to his character.

Always sensitive to context—to be expected from one who experiences every unaccommodating wrinkle in the built environment—Walker’s work is always sited with discretion (careful reading of a given space) or aggression (free-standing works, often gleaming stacks of glass designed to produce powerful geometric configurations, sometimes with a central well which plumbs the work’s depth). He is always aware—as his architectural heritage may remind him—of the moving spectator. Walker’s four-foot Modular scale, his Vitruvian Man, ends up questioning the spectator’s habits, conventions of viewing, and ultimately his or her self-image. This is a considerable achievement. One of many possible examples: Louvre, 2000, a row of angled glass and mirror, is set at four feet high. Serially mirrored in the clefts and angles of the reflective surfaces, half the spectator’s body is eclipsed. What other advantaged or disadvantaged community would require the world to be re-designed? Basketball players, for whom the scaling of the domestic environment is unsympathetic. With them, Walker has a lot in common. The rest of us, of various sizes in between, make do with design’s certified templates projecting its versions of our height and substance.

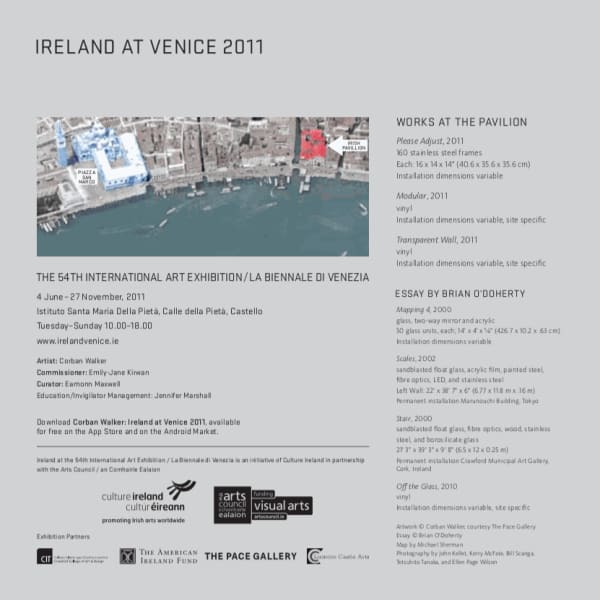

The Irish Pavilion at Venice gives an international audience the opportunity to see new work by this fascinating mid-career sculptor. His major work for Venice, Please Adjust, is a stack of interlocking stainless steel open cubes, skeletal frames, which, in their changing configurations, respond to gravity’s gentle pull. Sol LeWitt’s rational order of cubes has been both imploded and exploded. The stack is subject to alteration at each installation, so that no master image of the work appears. It remains as subtle and elusive as a reflected image, as do the athletic permutations, reversals, and serialised vinyl drawings Modular, and Transparent Wall, the artist has applied to the windows of the space—all scaled of course, to his unyielding standard.

Brian O’Doherty